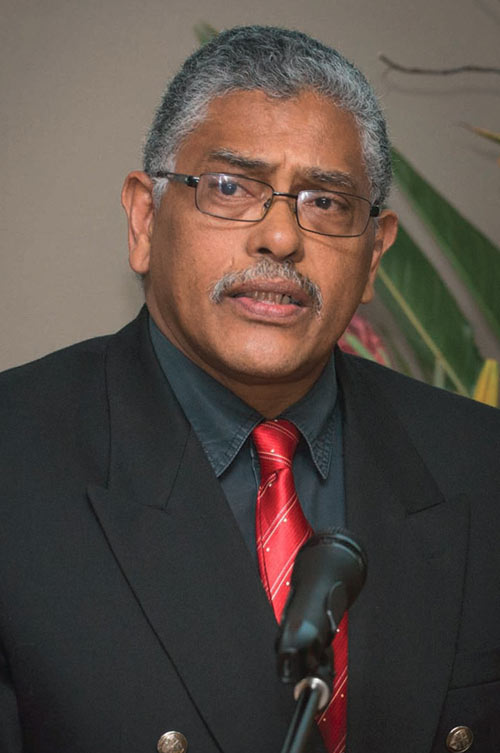

Professor Hein Willemse

Professor Hein Willemse

Professor Hein Willemse of the Department of Afrikaans in the Humanities at UP opened a recent paper on the hidden histories of Afrikaans with these words. He has been researching literature and culture among black Afrikaans speakers for close on 40 years – unknown texts, written about marginalised black Afrikaans writers, and doing oral culture fieldwork among the Afrikaans poor of Namakwaland and Namibia.

He writes that one of the undoubted successes of Afrikaner Christian nationalist hegemony was the creation of the myth that the nationalists, and only they, spoke for those identified as ‘Afrikaners’, and that their worldview was the only significant expression of being Afrikaans-speaking. In all of this, language historians, nationalist politicians, the media and school curricula have chosen to tell one story. It was this story that non-Afrikaans speakers – individuals, communities and institutions outside the Afrikaans speech community – have accepted as the only story. Afrikaans became indelibly identified with Afrikaner nationalism. Not only did nationalist functionaries and culture brokers suppress oppositional and alternative thought within the Afrikaner community, they also minimised the role and place of black Afrikaans speakers in the broader speech community.

In the late 1970s academics – and black Afrikaans-speaking academics especially – understood that a different story needed to be told. At the very least, one that tells of a more encompassing history, a history that explored the life and culture of those marginalised.

Along with colleagues at the University of the Western Cape, Professor Willemse had organised and participated in the Black Afrikaans Writers’ Symposium and over the years they have published three volumes of collected papers: Swart Afrikaanse skrywers (1986), Die reis na Paternoster (1997) and most recently ’n Vlag aan die tong (2015). The latest collection brings together the voices of a variety of writers and the peer-reviewed papers of literary scholars on significant black Afrikaans writers.

In 2007 Willemse published a book on selected black Afrikaans writers, called Aan die anderkant. Swart Afrikaanse skrywers in die Afrikaanse letterkunde. In 2011, he and a colleague at the University of KwaZulu-Natal, Suleman E Dangor, edited Achmat Davids’ book The Afrikaans of the Cape Muslims, which deals with the rich history of the people who were among the first to write their religious texts in Cape Dutch and named their language ‘Afrikaa’.

On the impact of these texts and his writings on the development of knowledge of the ‘hidden histories’ of Afrikaans, Willemse says that primary research takes time, and that will take time to filter through to the broader public. His colleagues in the Department of Afrikaans at UP have done research on black Afrikaans communities around Pretoria and parts of northern Limpopo in the 1980s and that research has now found its way into the specialist literature.

Recently, Professor Willemse delivered the keynote address at the unveiling of a bust of the writer Arthur Fula at the National Afrikaans Literature Research Centre in Bloemfontein. Fula, whose mother tongue was Sesotho, wrote his Afrikaans language novels in the 1950s. “This recognition of Fula comes late but at least it tells us that there is a wider understanding of the multiplicity of stories and voices and a recognition of the diversity of people who speak, live and write Afrikaans. However, the greatest challenge remains the persistence of the old nationalist myths on Afrikaans. Quite often those myths speak of ignorance and today people keep them alive for their own political ends.”