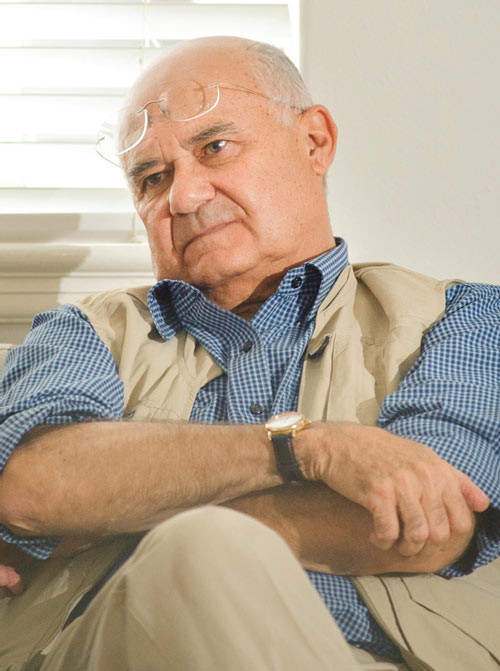

Professor Charles van Onselen

Professor Charles van Onselen

Charles van Onselen, Research Professor at the Centre for the Advancement of Scholarship, is an A-rated scientist and author of articles in leading international journals, and several books on southern African history.

His latest book, Showdown at the Red Lion: The Life and Times of Jack McLoughlin, 1859-1910 (Jonathan Ball, 2015), formed the basis of an expert lecture delivered at UP: ‘Sunny Places for Shady Characters – The Making of Working Class Cultures in Southern Africa’s Mining Revolution, c.1886-1914’.

In his lecture he elaborated on South Africa’s industrial revolution occurring in a Calvinist-dominated and labour-repressive state linked via a strategic corridor to a Catholic regime in Mozambique that was markedly less morally repressive. Third parties used these disparities in state power to exploit the legitimate or illegitimate demand for certain products or services for private or public financial gain. He suggests that the resulting patterns of social control and collective working class behaviour are best understood as liminal phenomena operating from within this Calvinist-Catholic nexus. By tracing the historical links between Johannesburg and Lourenço Marques, the rise and decline of the trade in alcohol and opium, or the provision of outlets for gambling and prostitution, his lecture (and book) illuminate the dark underside of southern Africa’s industrial revolution in new ways.Professor van Onselen writes that with minds stuffed with facts and dates, biographers then scurry off to their laboratory-studies where they use the historical imagination, ink and paper to place the dead back in the context of lives lived in times long forgotten. They do this because they know that the alchemy of the book will enable souls seemingly gone to reach out from beyond the confines of the printed page to fascinate, educate and inform the literate about worlds lost. History allows readers settled within the comfort of their favoured retreats to time-travel into dangerous, distant or forbidding places they would otherwise never visit. It is a kind of magic that allows authors to penetrate the consciousness of the living through the dead.

The remains of Jack McLoughlin’s skeleton, minus an arm and with the neck broken, now lies lost beneath an unmarked grave in Pretoria’s Rebecca Street Cemetery. The Manchester-born Irishman’s arm was shattered and then amputated after a failed attempt at escaping from prison in Potchefstroom, in 1890. Dogs roam across the grave, plastic bottles bedeck it and vagrants urinate around there. It was where, back in 1910, the state rid itself of the bodies of those who it had hanged by the neck until they were dead. Nobody loved him then, nobody cares for him now – unless you choose to read about him.

If you want to breathe life into what is left of the man’s memory and restore some of his dignity in death, you need first to visit the national archives, that graveyard in-the-making of what should be our well-preserved document-based history, and retrieve the 1909 record of his trial for murder. From the record it is clear that, in the 15 years between the moment that he shot George Stevenson behind the Red Lion in Johannesburg, in 1895, and the day that he was executed in 1910 – and indeed long before that – the condemned man had led an extraordinary life. In an era dominated by ideologies of hyper-masculinity replete with oath-bound notions of honour he had, by his own lights, attempted to retain both his independence and sense of self-worth in countries around the Indian Ocean rim – in Australia, India, New Zealand and southern Africa. It is important because, how can one comprehend fully the struggle for female equality and women’s rights in the late 20th and early 21st century unless one understands the codes of masculinity that accompanied the ravages of colonialism and imperialism? Showdown is the story of one such man’s struggle for life as the state reached across an ocean to try and snuff out his existence in those times.

The delight of biography, properly done, lies in its unparalleled ability to conjure up lives in eras past so as better to understand the deepest sources of the complexities, contradictions, ironies and paradoxes that beset the modern world. Social historical research is rewarding because it provides curious, literate men and women with the opportunity to position themselves more intelligently for the journeys that lie ahead. You only know where exactly it is that you are bound for once you understand where you are – and you can only know that once you appreciate fully the path already travelled.

Rebecca Street Cemetery in the City of Tshwane, the site of Jack McLoughlin’s unmarked grave

Rebecca Street Cemetery in the City of Tshwane, the site of Jack McLoughlin’s unmarked grave